During my time in Central Queensland, on daily trips to and from work, I saw these little steep and narrow mountains on the horizon. At first I thought they were stockpiles of coal so weird was their shape in contrast with the rest of the sprawling flat country.

But after a while, in clear weather, it would become apparent that these were no man-made structures.

These mountains fascinated me. Somehow they represented freedom and individuality amid boring, flat, barbed-wire fenced farm paddocks. So it is no wonder that when my contract was finished I decided to stay in the area and check them out.

On Sunday morning I did a bit of a research to find out how I could get near these mountains in my car.

I found on Google maps that there was a very convenient sealed road passing by the range and there was even a road going up one of the mountains – Mt MacArthur.

I thought it was perfect and packed up my bags to go and do some photo shooting from the top of Mt MacArthur.

Imagine my disappointment when I got to the mountain and found a locked gate blocking the road that led up. Close by, Mt MacArthur turned out to be a glorified hill with some communications structures – antennas and such up the top. That’s why there was a road going up – to give vehicle access to these structures.

This has completely killed the adventure and even though I could hop over the gate and walk up the road to the top, my heart was no longer in it.

I continued driving along until the mountain behind Mt MacArthur came into view.

Now this one looked completely different – tall and steep with beautiful yellow fields at the bottom and inhospitable rugged top. It was beautiful. It was calling me. It had my name written all over it.

I put on my mine protective gear: the high-viz orange shirt and steel-capped boots, which were conveniently left in the boot of the car, threw on my backpack with some provisions and started towards the mountain.

It was a 4 to 5 kilometre walk and on the way I had to jump 5 or 6 barbed-wire fences that were separating paddocks and cross two dried-up creeks before I reached the foot of the mountain.

As I was approaching it, I assessed that the Eastern slope was probably a better way up.

I began my assent through the almost solid bush. Apart from some cow dung on the way and some wallaby droppings up the slope there was no sign that anyone has ever been here before.

I made my way up slowly, arduously trying to avoid the multiple traps that the bustling local spider population have left for the unwary tourist.

I have climbed hills and mountains before but never ones that did not have any semblance of a path. This was pristine wilderness and it added greatly to the sense of adventure.

The view that was opening to me was very nice indeed and it was worth stopping every now and then to admire the scenery.

The mountain itself did not disappoint with it’s variety of interesting bushes and trees. I went on climbing the inhospitable slope. I made it a game to ask myself “how do I get up the top?” and answer “one metre at a time”.

It was quite fun until about two-thirds of the way up I hit a near-vertical wall of stone.

The dense bush prevented me from going around. There was an impossible wall on my left and a crevice on my right so I figured that, save climbing all the way down and trying to find another route, the only way was up. So up I went. Like an experienced rock climber, which I was not, and without any safety gear. The drop down would have been my last thrill in this lifetime.

About half-way up the wall I found I could not go up any further. There were no foot or hand holds i could use and climbing down even a metre seemed impossible. My muscles began to turn into jelly. Panic began to set in. I was all alone stuck on a vertical wall with a few seconds of strength left.

It was interesting to observe myself dealing with this situation. I very sternly told myself not to panic. I told myself that there is always a way. I told myself that there was no way I was going to die trying to scale a pathetic little mountain and it was just not glorious enough death for me. I told myself that I had a son to go back to and there was no way I was going to miss that appointment.

Well, lo and behold: the strength came back and the required foot and hand holds revealed themselves a couple of metres to the left. I still had to climb down a little before I could reach them. I was so relieved I found the way that I forgot all about how dangerous it was to climb down and just did it without thinking. That has probably saved my life. Had I realized the danger, I’m not sure I would have made it.

Finally, I made it to the top.

Strangely, I didn’t have much of a sense of accomplishment. The view was just as good as it was one third of the way up and there was nothing remarkable about the top of the mountain so I just sat there eating my Cesar salad and keeping an eye on a huge three-metre eagle that was circling above me, probably thinking that my orange shirt was rather attractive.

I put my hoodie over so as to make myself less desirable to the eagle.

Another thing that must have contributed to the lack of enthusiasm on my part was the fact that I did not discover a cable car waiting to take me down, which I was secretly hoping for on the way up.

I knew the job was only half-done and began to look for an easier way down. I knew I didn’t want to go back the way I came. There was no much visibility from the top and there was no way to tell which slope would make an easier descent. So I just ennie-meenie-manie-moed and started in the direction I felt was quickest. From up there it all looked the same.

Needless to say I’ve chosen the second-worst path down. I was right about one thing though – it was the quickest way down. Or it would have been if it wasn’t for the thick, spider-infested bush that covered that slope.

Nevertheless, I made my way down sometimes faster and sometimes very slow, once again playing the “how do I get down? One metre at a time!” game.

I slid, I fell, I ran and I crawled. I twisted my ankles and my wrists so many times it didn’t matter anymore.

I got caught in spider web an squealed like a girl trying to shake the huge 5cm bastards of my shirt.

A third of the way down I hit another near-vertical stone wall but this one was no match for an experienced faller down that I’ve become.

About 50 metres to the bottom I found myself in a narrow crevice down which water would fall down after the rain. I was absolutely right – I chose the quickest way down. So did the water which has polished the vertical rock clean and smooth all the way down. Nothing to hang on to or rest a foot on.

I screamed swear words in frustration. I would have to climb back up – there was no other way. I looked at the sun and judged that I had another hour – hour-an-a-half before the nightfall. Going up and trying to find another way would set me back too much.

I looked down in desperation trying to find a way. The rock was smooth for a good 30 metre drop and no way around it. But strangely I had a feeling that I could do it. I did not know how but I decided to trust that feeling. I put my camera in the backpack, threw my trusted spider stick down and went for it. Propping my legs and arms against the opposite sides of the waterfall’s crevice I inched my way down an impossible drop.

I was so relieved at the end of it that I didn’t even stop to take a picture of the drop. It was a race against the sun – even off the mountain I did not want to get caught in the dark before I found my way back to the road. There was another 4-5 km hike through waist-deep grass, corn fields full of spiky stalks and barbed-wire fences.

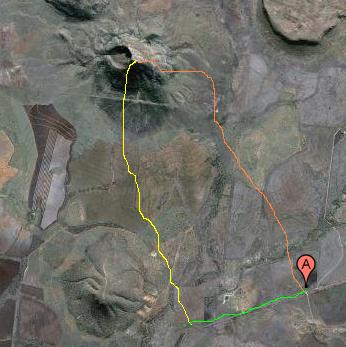

Here’s how it all looked like:

The A marker is where I left my car, the orange line is how I went up, the yellow line is how I came down and the green one was where I got a lift from the local farmer who was rather amused by my story.

By the way, you can see Mt. MacArthur down the bottom of the picture and if you look closely you can see the road going up it.

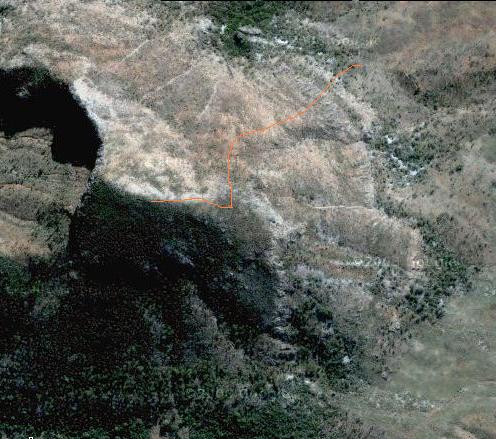

I named this article ‘On the importance of planning’ because after conducting a review of the trip I found that I did not choose the best way to go up and particularly not the best way down. Here is a close up of the slopes with the points where I had climb up or down vertical rock encircled:

I said I chose the second-worst way down because as you can see going down the Western slope would probably be even worse. It’s the bit that looks like a meteorite hit it or a giant has taken a bite out of the mountain.

Far better would have been taking the Northern slope for both the way up and down.

Had I spent a little time to plan this trip before-hand, I would probably save myself a few huge blisters, kicked in toes, sore ankles and wrists and lots of scratches.

Like I said, I did not feel any sense of achievement even after it was all over and I was driving in my comfortable car, finally giving some rest to my abused muscles.

As I was driving down the dirt road towards the civilization, the darkness fell and the headlights of my car would reflect in the eyes of the multitude of cows that were walking along the road looking very puzzled to see me, as if trying to ask “what the hell did you do all that for? Wouldn’t your time be better spent teaching others the benefits of planning?”